A guest post by Lorna Dillon

An arpillera is an art work, formed of appliqué or embroidery on a background of sack cloth. The word arpillera originally refers to the coarse woven fabric that is used for sacking. In the UK jute is the material that has traditionally been used for this purpose. In the US the term burlap is used to describe this kind of material. This cloth was commonly available in the 1960s and 1970s and some artists used it as a backing material for textile art. The Chilean artist Violeta Parra (b.1917, d.1967), for example, used jute as a backing material for bold woollen embroideries. Parra’s embroideries (often referred to as arpilleras) were an artistic hybrid, blending the conventional subjects of high art (historical, religious and domestic scenes) with the rustic aesthetic of needlecraft.[1] Parra exhibited her arpilleras in a variety of locations, from open-air art fairs to prestigious galleries; most notably she exhibited in the Museé de Arts Decoratifs in Paris in 1964. More information on Violeta Parra’s art can be found in my book Violeta Parra: Life and Work.[2]

Violeta Parra’s art is part of a long textile tradition in Latin America in which products made from wool, thread or fabric are often imbued with meaning. The ancient string work or ‘quipus’ used in the fifteenth century by the Incas, for example, helped with accounting and narrating stories. Likewise, belts woven by the Mapuche people in modern Chile contain motifs that have cultural significance, extending beyond the functional purpose of the item.[3] Similarly, the arpillera tradition uses symbols and motifs to narrate stories. However, the arpillera tradition uses simple techniques which are far removed from the technically complex woven fabrics that predominate in the majority of Latin American textile traditions.

In the mid-1970s a new kind of arpillera emerged in Chile, which typically differed from Violeta Parra’s embroidered textile art. These new arpilleras had more in common with patch-work and the activist, art-quilt movement that was spreading through the United States in the mid-twentieth century. These arpilleras, made by community groups in economically-deprived areas of Santiago, typically created images using the technique of applique rather than embroidery. Formed of scraps of second hand material, the arpilleras were a kind of advocacy art, which sought to convey the extreme hardship of living under a dictatorship.

In 1973 the Chilean government was overthrown in a violent coup in which left-wing politicians and activists were imprisoned, tortured and sometimes killed. People who opposed the regime were abducted by the military or police and taken to clandestine detention centres. In many cases, their relatives did not know where they had been taken and the abducted people were often killed in detention and would therefore never return to their communities. This phenomenon is known as ‘the disappearances’. According to Hugo Frühling, 2286 people were killed or disappeared in Chile between 1973 and 1989.[4]

Many Chileans sought asylum overseas. Those who were left in the country faced extreme hardships. There was a curfew and widespread poverty. The community groups who made the arpilleras did so partly to earn an income and partly to communicate the human rights abuses that were occurring in the country.

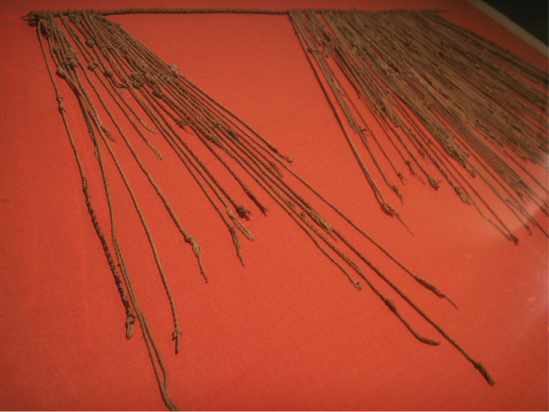

The image above is of an arpillera called the Hornos de Lonquén (Lime Kilns of Lonquén)[5]. The art work was created in 1979 to communicate the horrific discovery of human remains in industrial kilns near the town of Lonquén. The corpses were of 15 peasant men who had been arrested and disappeared in the first month of the 1973 dictatorship. The men had been members of an agricultural co-operative in the town Isla de Maipo. Their relatives had tried to find information regarding the whereabouts of the disappeared men, but were told by the authorities either that the men had escaped, that they had never been detained or that the individuals did not exist. In fact, the men had been held in detention for five years before they were burnt alive in the lime kiln. Their fate would perhaps never have been uncovered, were it not for a secret testimony given to a religious organisation known as the Vicaría de la Solidaridad. This testimony led to the search for evidence in the Lonquén region and the remains of the men were found along with scraps of their clothing. The Lonquén case was an important one in Chile, for it marked a turning point in the search for the disappeared; people began to realise that disappeared people were unlikely to still be held in captivity. They came to realise that the term ‘disappeared’ usually meant that the person would have been killed.

By presenting atrocities such as this in a work of art, the creators of the arpilleras (or arpilleristas) were able to communicate what was happening to the outside world and people overseas were able to buy something from the arpillerista communities, thus providing them with financial support as well as solidarity. This exchange was an important mechanism of international co-operation at a time when the Chilean press and television media were heavily censored, and freedom of speech was curtailed. The arpilleras managed to escape the censor’s gaze.

The original community arpillera groups were made up mostly of women, but some groups did have men in them. The practice of making arpilleras was extremely well-organised and the vast quantities of the works of art were exported.

On a much smaller scale, some of the Chileans who went into exile also made the odd arpillera. Overseas the practice tended to take the form of individual works of art made by people in the exile community. They were often made as gifts for friends or collaboratively to express their experience of exile.

Later the arpillera tradition extended to Peru. The model of using this art form as a way of denouncing human rights issues had proven success and Peruvian groups used it to convey issues arising from the war between the government and the rebel movement Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path).

In the last decades of the twentieth century and the first two decades of the twenty-first century, arpilleras continued to be made in Chile and Peru. Towards the end of the dictatorship period and after the return to democracy in Chile in 1989, the content of the Chilean arpilleras was driven more by commercial forces than advocacy. As a result, there was a move away from the politically-engaged images of the late seventies. At the same time, however, in countries like Colombia and Mexico where serious human rights abuses were occurring, other forms of textile art developed as a way of communicating displacement, disappearances and violence committed by state, paramilitary or insurgent forces.

In an earlier post, Jimena Pardo discussed an arpillera entitled We are seeds, which was made to denounce the disappearance of 43 students in the Mexico in 2014. The arpillera, which was made in the UK, demonstrates the way the arpillera solidary movement has grown, and it is a good example of the way arpilleras themselves are seeds. These works of art skilfully communicate atrocities. By communicating human rights abuses, they plant the seeds of hope for peace and justice. At the same time, they often plant an artistic seed. People who view the works of art often become compelled to create their own art of resistance, facilitate arpillera workshops or carry out some other act of solidarity, and it is in this way that the broader advocacy textile tradition comes to fruition.

Notes

[1] Images of Violeta Parra’s arpilleras can be seen on the Fundación Violeta Parra website and the actual works of art are exhibited in the Violeta Parra museum in Santiago, Chile.

[2] Lorna Dillon, ed., Violeta Parra: Life and Work (Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2017).

[3] Pedro Mege Rosso, Arte textil Mapuche (Santiago: Museo de Arte Precolombino, 1990), 12.

[4] Hugo Frühling and Wolfgang S. Heinz, Determinants of Gross Human Rights Violations by State and State Sponsored Actors in Brazil, Uruguay, Chile and Argentina 1960-1990. (The Hague, Boston and London: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers 1999), 465.

[5] This arpillera is part of the Conflict Textiles collection. Find more information about this textile here.

Lorna Dillon is an Associate Lecturer at the University of Kent. She facilitates the research network ‘War and Nation: Identity and the Process of State Building in South America 1800 -1840’. Lorna was awarded her Ph.D in 2013 by King’s College London. Her recent publications include Violeta Parra: Life and Work (Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2017) and “Religion and the Angel’s Wake Tradition in Violeta Parra’s Art and Lyrics.” Taller de Letras 59, (2016): 91-109. Lorna’s research interests include Violeta Parra; arpilleras; the Conflict Textiles collection; Britain Chile solidarity, and the translation of theatre and poetry.

2 thoughts on “What is an arpillera?”