By Christine Andrä, Berit Bliesemann de Guevara, Lydia Cole, and Danielle House

This text was originally written for and published by the Art and International Justice Initiative’s blog.

“No to impunity”: conflict textiles calling for justice

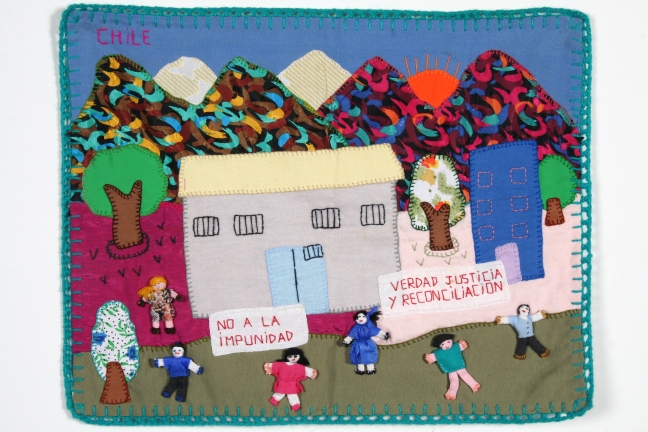

“No to impunity”, a protest banner exclaims. “Truth, justice and reconciliation”, reads another. These demands, made by Chileans resisting the Pinochet regime, have a familiar ring to us – all the world over, peoples’ struggles against the violence of military dictatorships and armed conflicts have been accompanied by urgent demands for justice. Yet the form these demands take here is an unexpected one: for the banners are stitched onto an arpillera, a three-dimensional textile picture composed of colourful scraps of cloth sewn onto hessian, complete with an embroidered frame.

In this post we introduce arpilleras and other conflict textiles and share some of our experiences of working with these textiles in the context of a dedicated exhibition. In keeping with ARTIJ’s themes, we also reflect on conflict textiles’ status as art, as well as on their potential, indeed their force, in pressing for (international) justice. As to the former question, we point out how conflict textiles complicate the very category of “art” – how they straddle divides between art, craft and activism, and how the medium of textile and the practice of needlework continue to be associated with femininity, domesticity and “mere” decorative purposes. With regard to the latter point, we describe the role that conflict textiles can play in trials and truth and reconciliation commissions, yet we also argue that their greatest value lies in the powerful work they do outside such formal justice processes.

Conflict Textiles and the Stitched Voices exhibition

As researchers with overlapping interests in the topics of violence, conflict, memory, and post-conflict politics, we came to work with conflict textiles through Stitched Voices, an exhibition we commissioned and co-curated. Dedicated to textile narratives of struggles against violence, injustice, and forgetting in different world regions, Stitched Voices was first displayed in the main gallery space of Aberystwyth Arts Centre in the spring of 2017. Since then it was shown – in slightly different compositions – in Birmingham and Uppsala. Stitched Voices consisted of a selection of textiles that were on loan from the international Conflict Textiles collection assembled and curated by Roberta Bacic, a Chilean professor of philosophy who has also worked for the Chilean Truth and Reconciliation Commission and for War Resister’s International, and with whom one of us had previously collaborated on another exhibition. Alongside the pieces loaned from Roberta, Stitched Voices also displayed textiles sourced from collectors, museums, artists and activists based in Wales, London, and Mexico. Accompanying the exhibition in all three locations was a programme of activities and events including textile-making workshops, embroidery sessions, film screenings, song and poetry events, roundtable discussions and academic workshops.

In our work for Stitched Voices as well as in research, exhibitions, and textile practice we have engaged in since, we have come to use the term ‘conflict textiles’ to refer to a wide range of textiles struggling for justice, memory and truth in the context of different kinds of political violence. Stitched Voices demonstrates the breadth of ‘conflict textiles’: besides arpilleras such as “No a la impunidad/No to impunity”, it also featured a Chilean quilt (“Hilvanando la busqueda/Stitching the search”), an installation of textile dolls from Colombia (“Long wait of the mourning women”), handkerchiefs produced by the Mexican movement Bordando por la Paz y la Memoria (Embroidering for Peace and Memory), sewn protest banners from Wales such as ”It’s No ******* Computer Game!” and the Aberystwyth Anti-Apartheid banner, parts of an international peace ribbon, as well as textile and mixed-media artworks such as “Disappeared” by Irene MacWilliam, a textile artist focused on themes of conflict and violence, and “Continuum” by Eileen Harrisson, a mixed-media artist who is currently pursuing a practice-based PhD at Aberystwyth School of Arts and whose work often deals with her experiences of the Troubles. The term ‘conflict textiles’ is applicable beyond the textiles featured in our exhibition. Since we first began our work on Stitched Voices, we have been encountering textiles protesting against violence and injustice in multiple global contexts, from the Palestinian History Tapestry to Afghan war rugs and from the Hmong’s embroidered story cloths to guerrilla knitting.

Conflict textiles communicate on several levels. In one sense they are documentary. Arpilleras, for instance, describe and depict instances of protest, torture and forced disappearance that really took place, with each textile doll sewn onto them representing an actual person. In a similar vein, arpilleras might function as another kind of what Nishma Jethwa has called “story documentation” – they document peoples’ lived experiences, memories and stories. Yet conflict textiles are more than just documentary. For in the slow act of textile making – in the threading, the cutting, the stitching, the weaving – stories are not merely recorded, but actively developed or, quite literally, “spun”. This process can be emotionally, socially, and politically transformative for those who have experienced violence against themselves or members of their family. Likewise, viewing, touching, and participating in the making of conflict textiles can be transformative for those who have not lived through such experiences. In visitor feedback and at our events, for instance, many of our exhibition’s visitors spoke of their feelings of empathy and solidarity.

Complicating what “art” is

Conflict textiles occupy a difficult relationship with the category of art. On the one hand, they are made with a creative desire characteristic of art, as Robert Golden has argued, “to change the material in front of you and the world around you.” Yet on the other hand, they complicate attempts to define what ‘art’ is, how and by whom it is produced, and how art can ‘work’ for justice.

Only few of the makers whose pieces we exhibited have a background in fine art and see themselves first and foremost as artists. By contrast, the majority of our textile-makers are relatives of the disappeared, political activists, or understand themselves as craftspeople. Many of these textile-makers even reject the label ‘art’ outright.

These differing views on whether conflict textiles constitute art map onto broader debates in the art world about gendered understandings of aesthetic and form. Though textile work has increasingly been incorporated into what might be considered high art, it is still a devalued form of expression because of its associations with women’s domestic labour and decoration. Yet, practices of stitch have long been employed, often by women, to speak about their everyday experiences and the politics implied therein.

When used to protest injustice and violence, textile practices are sometimes successful precisely because they fall outside the category of ‘art’ as traditionally understood. The Chilean arpilleras are a good example of this: during the early years of the Pinochet dictatorship, the medium of stitch enabled people to denounce the regime’s human rights violations in a form which, because of its association with femininity and domesticity, was seemingly inconspicuous and therefore more easily concealed, hidden, and smuggled out of the country.

In other instances, conflict textiles are politically effective because they unsettle or even subvert gendered expectations according to which textile crafts, in contradistinction to art, are made by women to speak about ‘women’s’ issues. “It’s No ******* Computer Game”, for instance, was co-created by Thalia and Ian Campbell, a couple who have been jointly designing and sewing protest banners since the 1980s. Originating from a very different context, while some of the embroidered handkerchiefs from Mexico record victims of femicide, the majority of them commemorate victims of the ‘war on drugs’ of all genders. These different examples demonstrate how war, conflict, and political violence are fundamentally imbued with gender – and show that needle and thread can be a powerful medium for people of all genders to protest these injustices.

Conflict textiles as a force for justice

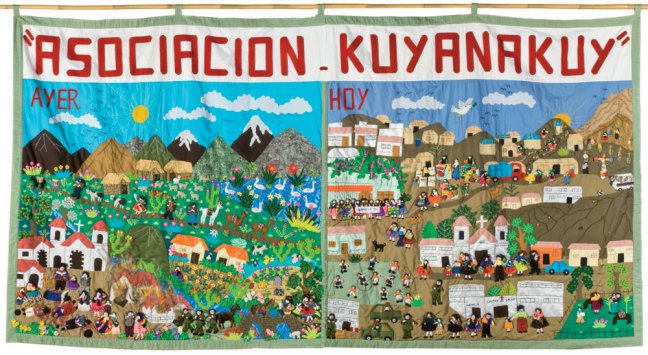

Conflict textiles speaking of human rights violations and other experiences of violence are sometimes incorporated into formal post-conflict processes for justice, truth and reconciliation. For instance, during the proceedings of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the indigenous women’s collective Asociación Kuyanuka provided testimony through an arpillera entitled “Ayer – Hoy” (“Yesterday – Today”). In this case, the arpillera’s makers wanted to contribute to the TRC’s proceedings, but were, as Elsie Doolan explains, “intimidated by the prospect of providing [testimony] in such a formal venue and in Spanish”. They therefore decided on textile as an alternative medium of expression. The example of “Ayer – Hoy” shows the potential of conflict textiles to facilitate wider participation in formal justice processes in the aftermath of violence.

The vast majority of conflict textiles, however, are made and used by people outside of formal procedures to voice their desire for justice and to document and further their struggles for justice’s realization. In this broader sense, the ways in which conflict textiles work as a force of justice vary depending on the positionality of their maker(s). Among the pieces featured in the Stitched Voices exhibition, we can distinguish two kinds of textiles based on their proximity to or distance from the events they speak of.

First, there are conflict textiles speaking directly of and from the personal experience of their makers. Made by people living many different kinds of violence, conflict, and human rights violations, these textiles are an immediate response to their makers’ harrowing experiences. These kinds of conflict textiles serve multiple functions. They record and evidence what is happening to their makers. They help to forge new connections, to create and sustain communities and social movements, and to construct alternative political imaginaries. Sold transnationally to solidarity groups, some of these conflict textiles also become a means of communicating with global audiences and of generating a modest income for their makers.

“No a la impunidad/No to impunity”, the arpillera depicted at the top of this blog post, is a good example of this first kind of conflict textile featured in the Stitched Voices exhibition. Produced during the final years of the Pinochet regime in Chile and made for export, “No a la impunidad/No to impunity” depicts women’s protests against Law 2191, also called the Amnesty Law. In 1978, the Pinochet regime passed Law 2191 to protect the suspected perpetrators of grave human rights violations during the regime’s first five years from being brought before the court. Twenty years later, Chile’s Supreme Court ruled the law inapplicable to the kinds of crimes it sought to exempt from prosecution. This opened up the possibility of bringing cases of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, torture, and systematic arbitrary detention to trial before civilian courts. While far more than 1,000 cases have been tried since then, Law 2191 itself remains valid – thus exemplifying the continued significance of arpilleras such as “No a la impunidad/No to impunity” and the stand they take in struggles for justice.

Another example of a conflict textile speaking directly from the personal experiences of their makers comes from present-day Mexico, where various groups of relatives and activists embroider cotton handkerchiefs to render visible the deaths and disappearances perpetrated by the different parties to the so-called ‘war on drugs’. The handkerchiefs featured in Stitched Voices were lent to us by Fuentes Rojas Collective, FUNDENL Bordamos por la Paz Nuevo León and Bordados por la Paz Puebla. Regularly meeting in public spaces such as squares and parks, these groups stitch one handkerchief per victim. Besides documenting and denouncing, the act of making also serves these embroiderers to reconnect with their killed or disappeared loved ones and to demand justice for these crimes.

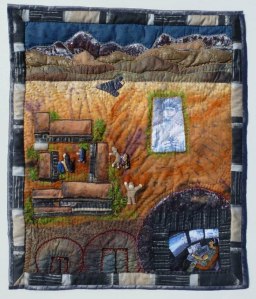

Second, our exhibition also featured pieces made by artists and activists situated at a distance to the events that their textiles resist and speak out about. Individually and collectively, these makers use stitch as a means for expressing their solidarity and for drawing attention to human rights violations in global contexts. Highlighting the misuse of drones in the ‘war on terror’, Deborah Stockdale’s “Digital Death” is an example of a conflict textile made by an individual artist at a distance to the events it depicts. The textile references “#NotaBugSplat” – an artwork which features a large portrait of a child who is reported by the Foundation for Fundamental Rights to have lost both parents and two younger siblings in a drone attack. This artwork was installed in a field in the heavily-bombed community of Khyber Pukhtoonkhwa in Pakistan and was big enough to be visible to a drone operator. Speaking out against the dehumanizing effects of drone warfare, which it perceives to be a problem at a global scale, “#NotaBugSplat” seeks to bring to our attention “the innocent civilians killed by mistake in drone strikes.”

Inspired by these examples, we decided to also offer our exhibition’s visitors a chance to embroider in solidarity. In a corner of our gallery, next to a clothes line carrying the handkerchiefs from Mexico, we installed a second clothes line onto which further handkerchiefs embroidered by our visitors could be hung, as well as two armchairs and a wicker basket filled with already-marked handkerchiefs, red thread, needles and scissors. In addition, we ran weekly embroidery sessions in the gallery (or, weather permitting, just outside the Arts Centre). One of our visitors recounts: “I am soon lost in a task that is only a few letters long. How much more then must this act of devotion, of willful remembrance, mean to the people who have experienced the appalling violence, bereavements and unknowingness?”

Concluding thoughts

In our work with conflict textiles, we have been impressed with the way that these textiles tell difficult truths, naming perpetrators and representing specific massacres and torture prisons. It is this directness, together with the materiality of the cloth and thread and the embodied process of making, that makes conflict textiles a particularly strong force for justice. The majority of conflict textiles are not elicited by or produced in response to institutionalized justice processes such as trials and truth and reconciliation commissions. We believe that conflict textiles’ greatest value lies not in their potential to become tools in such formal processes. Rather, it lies in the different starting point that conflict textiles offer to those of us who seek to think about international justice in new ways: a starting point that rests with people and their concrete struggles for justice in a global context which consists not only of states and institutions, but also of transnational solidarities.

Featured image

“No a la impunidad/No to impunity”, Anonymous, Chile, ca. 1980s. Conflict Textiles Collection. Photograph: Tony Boyle.

About the authors

Christine Andrä is a Post-Doctoral Research Assistant on the project “(Un-)Stitching the Subjects of Colombia’s Reconciliation Process”, based jointly at Aberystwyth University (Wales) and the University of Antioquia (Colombia).

Berit Bliesemann de Guevara is a Reader in International Politics at Aberystwyth University.

Lydia Cole is currently an Associate Lecturer at University of St Andrews where she was lead commissioner of the exhibition “Threads, War and Conflict”; she will soon be joining University of Durham as Post-Doctoral Research Associate on the project “The Art of Peace: Interrogating Community Devised Arts-Based Peacebuilding”.

Danielle House is a Post-Doctoral Research Assistant on the project “Cemeteries and crematoria as public spaces of belonging in Europe: a study of migrant and minority cultural inclusion, exclusion, and integration”, at the University of Reading.